Once, in the mid-1980s, I was invited by a black undergraduate student group at Yale to lead a fireside discussion in one of the residential colleges. I was bemused to learn that the group had planned a half-hour break in the program so they could repair together to watch that week’s episode of The Cosby Show. As I sat in the common area and waited for their return, it occurred to me that they were at least in part modeling the behavior of upper-class black adults—much as some True Blue white male undergrads would practice being their fathers in the ivied preserves of Yale.

Those students and their general cohort were on the leading edge of a new, appropriately race-conscious, post-segregation–era black upper class. They were already selecting out just whether and how their class consciousness and race consciousness should combine. At around the same time, such students were struggling to navigate what it meant, how it would be possible, to be black and upper class in an integrated world. Lorene Cary’s thoughtful 1991 memoir, Black Ice, captured one strain of this response, which was for basically middle-class, or the already diminishing numbers of lower–middle-class, students to adopt “hood” personas. Via this cultural alchemy, urban school nerds were transformed into streetwise corner boys and girls in the cloisters of elite prep schools. Others lamented the alleged injustice entailed in the project of defining and enforcing the reigning terms of racial authenticity; why should those who claimed impoverished “ghetto” backgrounds be the de facto arbiters of true cultural blackness?

Meanwhile, auguries of how these tangled race and class identities and affiliations might be harmonized were already turning up. A year or two before my encounter with the Cosby moment, a very bright, self-assured undergrad asserted emphatically in a seminar I was teaching that the purpose of the civil rights movement had indeed been to allow her and people like her to go to Yale and then to work at Morgan Stanley, which she was preparing to do.

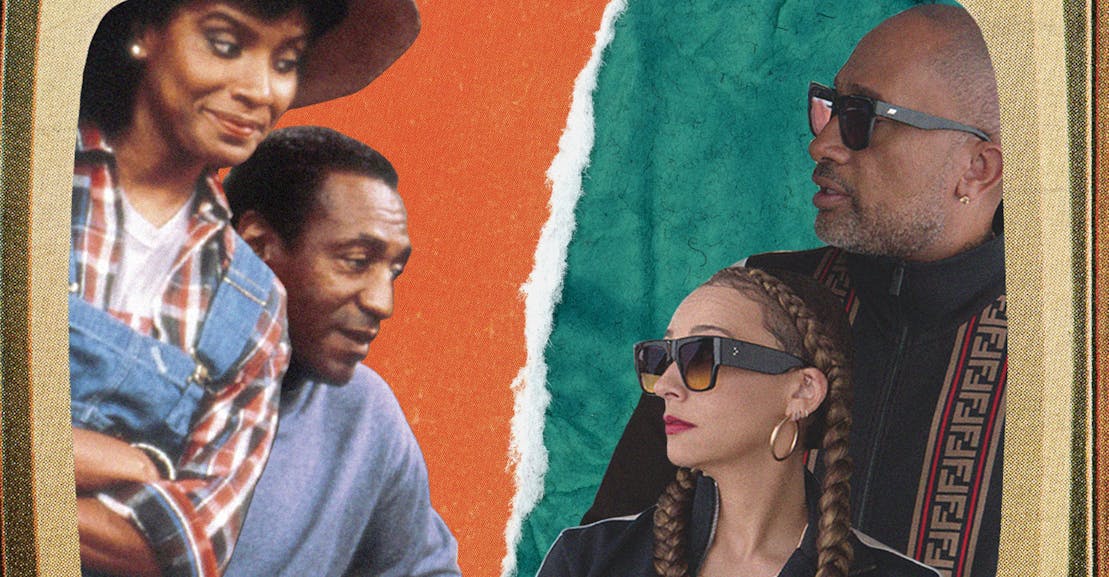

The Cosby Show, certified as it was by black psychiatrists, provided appealing black upper-class family role models. Its content was deemed wholesomely aspirational, not only for the future but also for the past. For those who did not come from upper-status backgrounds, Clair and Cliff Huxtable were the parents they were supposed to have had for the class position they assumed would be theirs. In that sense, the Cosbys provided black bourgeois aspirants a powerful shared (if imaginary) social background that validated their class position by projecting it backward in time. In other words, The Cosby Show worked for its aspirational black middle-class audience in much the same way that Merchant-Ivory films provided their professional-managerial class devotees a vicarious Edwardian-era bourgeois lineage.

Between the Huxtables’ heyday and the Obama presidency, popular culture tracked the new black upper class’s movement, as it traversed the critical odyssey from being a class in itself to becoming a class for itself. In 1994, journalist Ellis Cose published The Rage of a Privileged Class, which both marked the proliferation of a black upper-middle class and the particular racial frustrations that that stratum experienced. A spate of light films and rom-coms in the 1980s and 1990s—Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It and School Daze, the Hudlin Brothers’ House Party series, Sprung, The Inkwell, Waiting to Exhale, to mention only a few—played in more or less muddled ways with the tensions between racial identity and class aspiration. And the hit sitcom The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air took up the same themes on the small screen. This emerging genre stood out in striking contrast to the simultaneous proliferation of naturalistic urban pathology/underclass films, such as Juice, Sugar Hill, Jason’s Lyric, New Jack City, Menace II Society, and John Singleton’s reactionary films Poetic Justice, Boyz n the Hood, and, worst of all, the 2001 Baby Boy. This narrative bifurcation—aspirational sagas of upward black mobility pitched against lurid accounts of ghetto pathology—continues largely undisturbed in today’s cultural scene.