On a brisk morning in late August 1942, Wendell Willkie—a corporate lawyer, failed presidential candidate, and media darling—got onto an airplane for a trip around the world. Soon, he’d be holding court with kings, premiers, the shah, as well as soldiers and civilians across Africa and Asia. As the Axis powers seized a terrifying amount of territory, Willkie had been dispatched by the president of the United States on an audacious, if vague, mission to introduce the U.S. to the world.

From his perch in the sky, Willkie saw the planet differently—a planet that could be. Looking down, there weren’t any nation states, or, in his words, “splotches of color” that you’d find on a map. The world was “small and completely interdependent.” Going abroad also gave him a unique vantage point on the different people of the world. Schmoozing with government officials in Chongking or mingling with ordinary Egyptians in cafés, Willkie witnessed firsthand the shared desires of people around the world: peace, freedom, self-determination, the fulfillment of material interests.

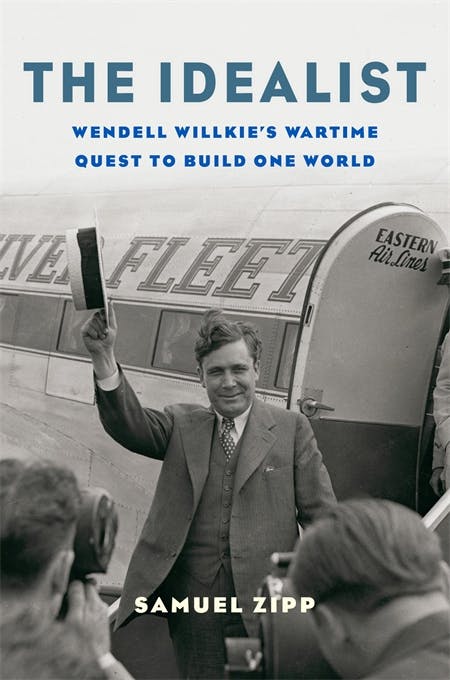

Wendell Willkie is an oddball in the history of internationalism. He wasn’t an intellectual. Nor was he a statesman. And he did not actively participate in any of the dozens of vibrant American organizations—such as the League of Nations Union—that sought to integrate the U.S. into the emerging interwar world order. Rather, Willkie spent those years working for big business and criticizing big government. But he was also, paradoxically, an avowed anti-racist (the NAACP even named its headquarters the Wendell Willkie Memorial Building). How this wealthy Wall Streeter became the star of internationalist efforts during World War II is a peculiar story. It is, as Samuel Zipp demonstrates in his exhilarating and timely new book, The Idealist, a story of media, technology, and a critique of empire that proved to be palatable—if only for a short while—for midcentury America.

Willkie leapt onto the national stage in the 1930s as a handsome, youthful force in the anti–New Deal coalition (which was, Zipp observes, an otherwise “dour and stuffy” bunch). Heading the third-largest electrical utility conglomerate in the country, he launched a public campaign against FDR’s plans to break up utility monopolies and provide cheap electricity to the impoverished Tennessee Valley. Willkie’s combination of a ferocious defense of free enterprise with small-town Indiana charm led one New Dealer to refer to him as that “barefoot boy from Wall Street.”

Willkie’s cause was unpopular. But it didn’t matter that Willkie led a losing fight against the New Deal. It had nudged him into the American spotlight. And that spotlight granted him, Zipp deftly argues, a novel form of power: celebrity. Thanks to radio, millions of Americans could tune in to hear his voice. In one radio appearance, on the highly popular Town Meeting of the Air, he trounced the assistant attorney general in a debate on whether the government should embrace the market. Magazines and newspapers covered Willkie obsessively: Puff pieces floated a presidential run, and photo essays in Life and Look made him a recognizable star. His hair—short on the sides, disheveled, a lock usually flopping over his forehead—was the subject of media attention. The New Yorker even interviewed Willkie’s barber.